Compassion Cultivation Workshop

:: Reason Digital | Workshop Design

Supervised by Hyper Island UK, Stacey Seronick (Creative leader at IBM) and Greg Ashton (Digital Strategist at Reason Digital)

Extracted from Master’s Thesis completed in Hyper Island UK

Challenge

How might we improve the sense of “empathy” in human-centered design processes?

My Approach

How might we make compassion comprehensible and actionable in human-centered design processes?

How might we make compassion comprehensible and actionable in human-centered design processes?

Tools Used

Tools Used

︎ shadowing research

︎ design thinking

︎ expert interview

︎ desk research

︎ sacrificial concept

︎ prototyping

︎ user testing

︎ learning arch

︎ Fogg behavioural model

︎ shadowing research

︎ design thinking

︎ expert interview

︎ desk research

︎ sacrificial concept

︎ prototyping

︎ user testing

︎ learning arch ︎ design thinking

︎ expert interview

︎ desk research

︎ sacrificial concept

︎ prototyping

︎ user testing

︎ Fogg behavioural model

Key findings:

Key Insight 1 |

The ambiguity of the terms have not been addressed and adequately clarified. Without a shared comprehension of “empathy” in contemporary design processes, actions will be built on a vague foundation that often leads to unclear instructions, time-consuming processes and immeasurable outcomes (Wispé,1986)

Key Insight 2 |

Tania Singer (2014) has proven that empathic activity activates regions of the brain that are associated with pain, which may lead to empathic distress or withdrawal of observer. Contrastingly, compassionate actions activate regions of the brain associated with love, warmth, reward, and affiliation that prompts prosocial motivation.

Key Insight 3 |

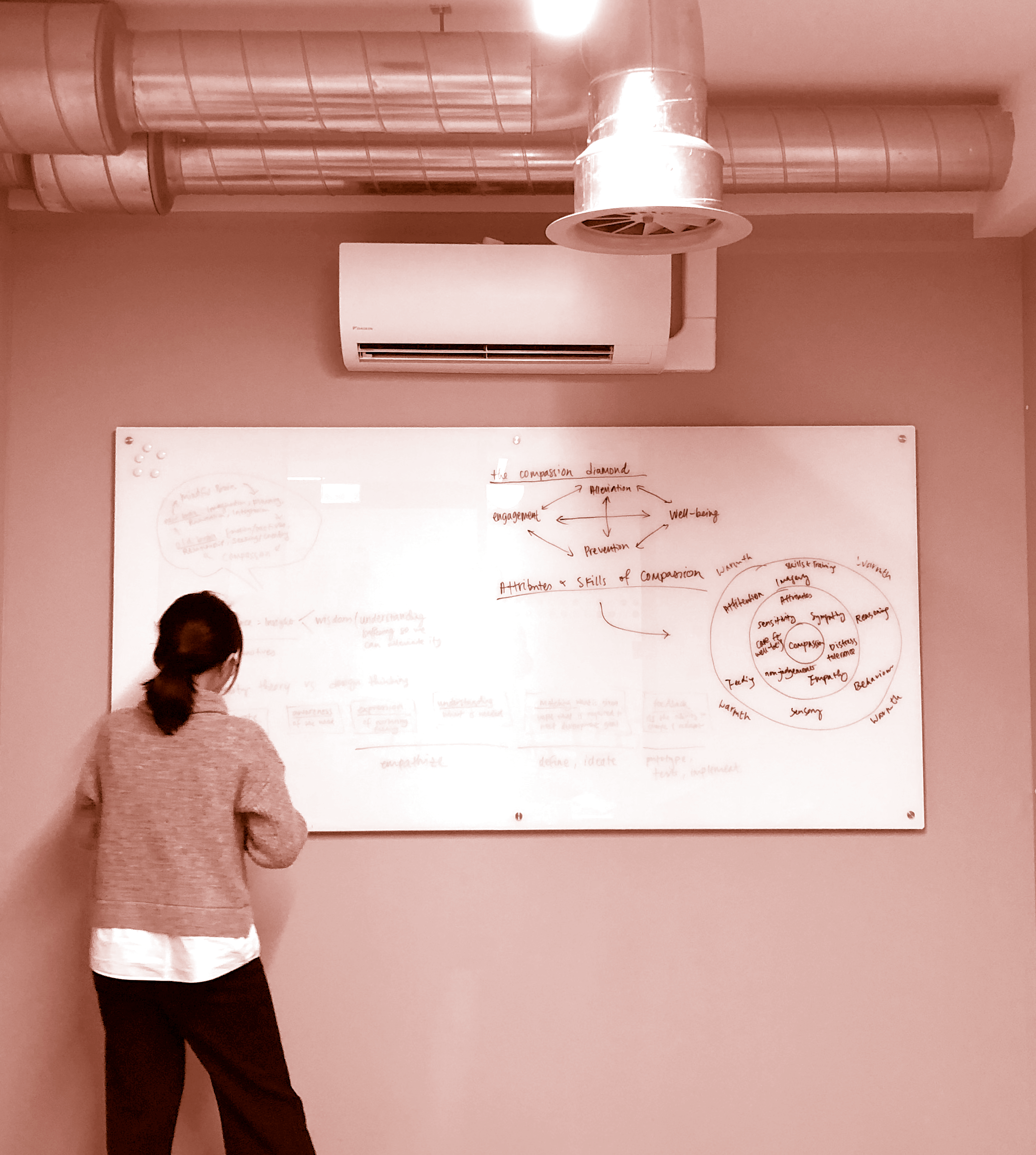

Social Mentality theory by Gilbert and Choden (2013) was compared to the Design Thinking process and Trompt and Hekkert’s (2019) Social Implication Design. It was noticed that mindful, compassionate engagement and alleviation are missing in the Design Thinking process. The missing steps are seen as pivotal factors that dictate altruistic helping actions.

Key Insight 4 |

Human-centred design practitioners are accustomed to engaging empathic skills during the research phase. However incorporating it before and after fieldwork is challenging, users were reported to be seen as merely “pieces of post-its.”

Key Insight 5 |

Rosenberg (2015) proposed ways to distinguish “Moralistic Judgements” that block compassion.

Moralistic judgements were referred to as an action that implies polarity labelling such as wrongness or badness when others did not act in harmony with one’s value. Rosenberg (2015) pointed out a difference between moralistic judgements and value judgements. For example, labelling “violence is bad” is categorised as moralistic judgement, where “we value peace” or “we are fearful of the use of violence to resolve conflicts” is considered to be a value judgement.

Prototype 1.0:

Component 1:

Self-compassion (to cultivate the capacity of compassion for others)

Exercise 1: Guided breathing meditation

Prototype 1.0:

Component 1:

Self-compassion (to cultivate the capacity of compassion for others)

Exercise 1: Guided breathing meditation

![]()

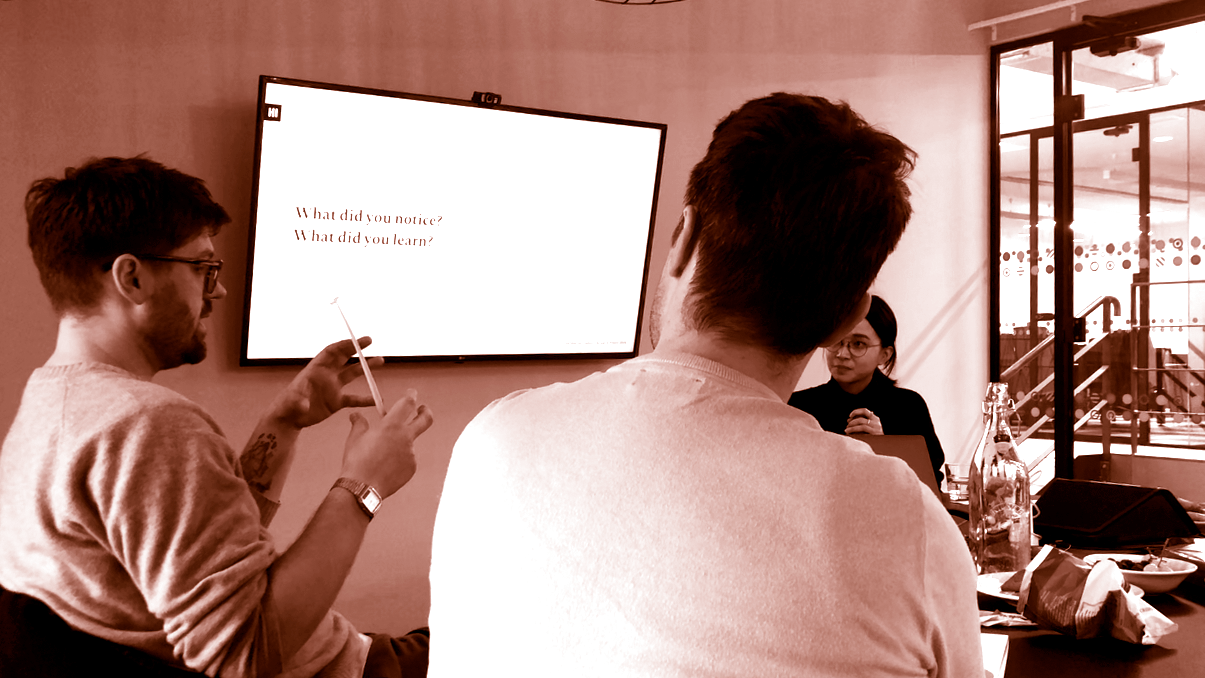

The workshop was officially tested on the 18th of November 2019, with a total of six participants from Reason Digital UK.

To activate compassionate attributes and skills mentioned by Gilbert and Choden (2013), one will have first to cultivate self-compassion (Goleman and Davidson, 2017).

During the landing session after this exercise, participants reported that the session “calms his head down”, and

the short exercise makes them felt “nice” about themselves.

To activate compassionate attributes and skills mentioned by Gilbert and Choden (2013), one will have first to cultivate self-compassion (Goleman and Davidson, 2017).

During the landing session after this exercise, participants reported that the session “calms his head down”, and the short exercise makes them felt “nice” about themselves.

Component 2:

Attention, awareness and sensitivity (to cognitive biases)

Exercise 2:

Part 1 of Compassion Transmission Download Sheet

![]()

A 15 minutes long Keynote presentation that guides participants through the key topics, the second invitation took place.

Component 2:

Attention, awareness and sensitivity (to cognitive biases)

Exercise 2:

Part 1 of Compassion Transmission Download Sheet

After a 15 minutes long Keynote presentation, the second invitation took place. Participants were presented with challenges to discover for the day.

They were instructed to spend five minutes to complete Part 1 of the CTD Sheet before moving into practising non-judgemental active listening exercise that nudges participants to be self-aware of their biases before entering a “fieldwork”.

Component 3:

Non-judgemental mind (towards users and team members)

Exercise 3:

Non-judgemental active listening

The workshop was carried out with a casual tone. The facilitator remains seated at all times to maintain eye-levelled conversations that aimed to decrease hierarchy between the facilitator and participants.

Participants were then split into their teams respectively to complete the non-judgemental active listening exercise. This exercise encourages listeners to remove labelling from observations that could block compassion.

Component 4:

Separation of observation from the evaluation (that allows transmission of compassion across team members, clients and s takeholders)

Exercise 4:

Part 2 of Compassion Transmission Download Sheet

Participants were instructed to pass around a “talking stick”, whoever holds it shares “what did they notice” after each exercise to land the learnings.

Moving forward, participants were introduced to the last invitation of the day — transmitting compassion by using the CTD Sheet. After downloading their findings and gathered insights individually, participants regrouped into their respective teams. Teams were expected to discuss and deliver a refined challenge statement that specified the issue.

What works?

As a result, Exercise 1 and 2 attracted majority positive feedback. Self-compassion and awareness of biases were significantly gained through the exercises.

Prototype testing results also revealed the interdependency of selected compassionate components. Through these testings, cultivating self-compassion is arguably one of the critical triggers of a compassionate mind. However, this is also often neglected in the observed design process.

Through the bird’s eye view of the observer, the workshop was kept casual allowing participants to be experimental throughout the session. The design of the challenges was a participant oriented that invited extensive conversations which is beneficial to the session in general. The landing sessions have helped participants in learning by listening to other perspectives.

As a result, Exercise 1 and 2 attracted majority positive feedback. Self-compassion and awareness of biases were significantly gained through the exercises.

Prototype testing results also revealed the interdependency of selected compassionate components. Through these testings, cultivating self-compassion is arguably one of the critical triggers of a compassionate mind. However, this is also often neglected in the observed design process.

Through the bird’s eye view of the observer, the workshop was kept casual allowing participants to be experimental throughout the session. The design of the challenges was a participant oriented that invited extensive conversations which is beneficial to the session in general. The landing sessions have helped participants in learning by listening to other perspectives.

What doesn’t work?

Due to the complexity of the exercises, instructions have to be clarified. Observations have to be specifically prompted to be withdrawn from evaluations. Through observations, the role of an “observer” within exercise 2 also appeared to be vaguely defined. The awareness exercise draws positive results. However, assumptions and biases were no longer visible after the exercise. Tangible ways to measure the success of each exercise is yet to be set up.

What can be done in the next iteration?

It should be emphasised that the workshop and the design of the tool are not assumed to be a “one size fits all” solution. The experiments have to be further examined and iterated to better fit into users’ day-to-day design practices.

Bibligraphy:

Gilbert, P., Choden. (2013) Mindful Compassion: Using the Power of Mindfulness and Compassion to Transform our Lives. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mindful-Compassion-Using- Mindfulness-Transform-ebook/dp/B009ZRR0RU (Accessed: 27 August 2019)

Goleman, D., Davidson, R. J. (2017) The science of meditation: How to Change Your Brain, Mind and Body. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Science-Meditation-Change-Your-Brain-ebook/dp/ B06Y2L858Z (Accessed: 24 October 2019)

Senova, M. (2017) This Human: How to Be the Person Designing for Other People. Amsterdam, Netherlands. BIS Publishers B.V.

Singer, T. & Klimecki, O.M. (2014) ‘Empathy and compassion’, Current Biology, vol. 24, no. 18, pp. R875-R878. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982214007702

Wispé, L. (1986) ‘The Distinction Between Sympathy and Empathy: To Call Forth a Concept, A Word Is Needed’, Journal of personality and social psychology, 50(2), PP: 314-321. DOI: 10.1037/0022- 3514.50.2.314

Tromp, N., Hekkert, P. (2019) Designing for Society. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Designing-Society-Nynke-Tromp/dp/1472568680 (Accessed: 26 August 2019)